Click here to read “Psalm One: Translation of the Song”

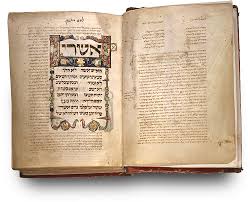

“Happy” — the first word of the first line of the first of King David’s praisesongs. The Hebrew, “ashrai”, voices the same opening note of joy as does the English, but, simply because the word “ashrai” starts with an “aleph”, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, the Hebrew underscores a sense of joyful beginning that the English word cannot.

The auspicious opening, whatever the language, makes even more jarring the repeated negatives that follow: “Happy the man who has not walked in the counsel of the wicked ones, and in the way of sinners has not stood, and in the gathering of the scornful has not sat” (v.1). What the first verse does, then, is to establish the dichotomy that is the song’s basis: the righteous, who delight in God’s teachings, will flourish like a tree — they will thrive and prosper (verses 2 and 3); in contrast, the wicked, who violate God’s teachings, will, like chaff, be swept away (verses 4 and 5).

Verse 3 is perhaps the most beautiful verse of the song: “And he will become like a tree planted by streams of water,

that gives its fruit in its proper time, and its leaf does not wither, and all that he does will succeed. “ The Hebrew of verse 3, “streams of water”, פַּלְגֵי מָיִם, suggests a forking, a stream that takes more than one direction. And, with this image, the song describes the two opposite directions of the wicked and the righteous. That both are imagined as water may indicate their common source: both beginning with the possibility of creativity but one leading to what the singer calls happiness, the stream following its natural course; the other, not merely to unhappiness, but indeed, to promise cut off, the stream blocked from further flow. The image of the dried-up stream is given another form in verse 4, the wing-blown chaff; thus, each image – the one implicit in Hebrew, the other explicit in Hebrew and in English – describe an extinction that allows neither growth nor rebirth.

But it is the striking phrase — “the assembly of the righteous ones“– in verse 5, that both re-iterates and explains the opposite fates of the righteous and the wicked: the righteous will form a community; the wicked will be outcasts. The negatives of verse 1 are thereby clarified: the righteous must not walk, stand or sit with the wicked; must not, that is, include them in their community. The progression — walk, stand, sit– reverses the natural order of human milestones: the infant first sits, then stands, then walks. Thus the wicked are diminished even by the verbs of the verse line.

The song that begins with the word “happy” ends with the word “lost”. A striking contrast. A warning, of course, to the wicked, but also to the righteous not to seek them out.

The Hebrew, however, once again goes beyond the English translation: the English song cycle ends song 1 at this grim point, “lost”. The Hebrew continues the cycle into song 2, so that the second song completes the first.

Surprisingly, Song 1 in King David’s praisesongs does not acknowledge him as the composer. Speculations based on history can be argued. But perhaps the song itself, in obscuring its composer, is putting forth, instead, its ideal of community.